This is the fifth blog in a series of posts in which I share what I am learning on my ‘journey’ towards obtaining a good milky way night time image. In my second year chasing down this aspiration, last year was dabbling and learning lots. This year, I want to ‘nail’ one or two good milky way landscape images. It’s a mission! Whether I can deliver on it or not is a moot point though!

If you have just arrived at this page, you may want to go back and read the first four posts in this series before reading this one. They sort of follow a logical order.

This blog post series shares what I have learned thus far to help encourage those of you seeking your first milky way image. Remember I am still at the very beginning of my learning journey. I am no expert. I claim no expertise in any way at all. A complete novice in photography and astrophotography. This entire blog is written from that perspective – a chronicle of my learning journey written by a beginner for other beginners. I know very little about anything frankly but therein lies the attraction. If I can do it with my very limited knowledge – then so can you; and probably better, as I am a rather slow learner at the best of times.

As always, if I have made any mistakes in my posts, I apologise. Please drop me a comment highlighting the issue and I will correct it immediately.

Please note: I will not be going into huge depth about how things work and why we do things the way we do. I’m not dismissing the importance of having a theoretical understanding – its critical – I’m just saying it’s not the focus of these blog posts. My aim, is to just get you out there, obtaining a first milky way image.

To help you achieve this, I will outline some simple answers to these questions:

1. What equipment do we need?

2. What advanced planning is needed to ensure success on the night?

3. What base settings can we use to help us get success?

4. What foreground composition considerations do we need to make?

5. What are the different techniques for getting a milky way photograph?

6. What do we need to consider if we want to do a milky way selfie shot?

7. How can we improve our milky way photography skills?

8. What is a ‘beginner’ workflow for post editing our milky way photographs?

Our fifth question then - What are the different techniques for getting a milky way photograph?

Up to now in this series of blog posts, I have been looking at doing single

exposure images of the milky way in a landscape setting. I touched

on occasionally, an alternative method, doing two separate images – one

exposed for the sky; the other for the foreground. We then blend these in post

editing to create one single image. At

its simplest, I call this technique ‘exposure blending’. We might

return to this technique later in the post.

However, there are a series of other techniques that we

could use to get our first milky way image. The key concept, isn’t it, is about

getting as much light as we can to our sensor through longer shutter speeds or

wider apertures – but this can bring the problems. Longer shutter speeds

introduce movement errors; wider apertures mean more of our scene will be out

of focus.

However, there are other approaches we can adopt which can

mitigate some of these impacts:

·

Star stacking

·

Using a star tracker

·

(Long exposure foregrounds)

·

(Focus stacking)

This is a post series by a beginner for beginners with

the aim of helping you obtain your first milky way landscape image.

Once over that first hurdle, you will be so keen to get other better images

that you will advance your own learning rapidly through YouTube tutorials,

on-line reading and plenty of practice. I am a very slow learner as you will

have already deduced from previous posts – so it takes me time to assimilate

and understand the basics!

So, lets investigate the technique of star stacking.

In star stacking – you take multiple photographs of the sky

and stars using short shutter speeds. These are then aligned in software which

creates a single final image – like an average of them all. This approach

reduces the amount of ‘noise’ in the image.

If you do deep sky astrophotography (my other passion) then

you will be familiar with ‘stacking’ multiple images. Stacking allows you to use faster shutter

speeds for pin point stars, and smaller apertures/higher F-stop numbers to

improve the depth of field in your image, the focus of the stars and reduction

of aberrations. It sounds counter

intuitive doesn’t it – faster shutter speed and narrower aperture – but because

you have taken lots of images and stacked them together – you are getting,

effectively more light into the final image.

What equipment will I need for star stacking?

·

Tripod and ball head

·

Intervalometer

·

(Lens warmer)

·

(Star Tracker)

What would be good starting settings for star

stacking?

Firstly, you compose your scene. See my

previous post about compositional tips.

Then we set our base astro settings. I start

with ISO 800 or 1600; F/2.8 and then a shutter speed that is matched to my lens

focal length (see my post on settings). I’ll go for a shorter shutter speed

than the 300 rule suggests for my crop sensor camera so that I can ensure

pinpoint stars. It is however a

balancing point as a shorter shutter speed means I will not get as much detail

out of the fainter areas of the milky way. ISO wise? You can correct exposure

during post editing. I find that on my camera if I use too high an ISO it

produces images with lots of noise – which is what I want to avoid.

How many photos to take? I take many in quick

succession. Nothing about camera position or composition gets changed between

exposures. I tend to take between 10 and 15, depending on my base astro

settings. 15 photos at 10” = 150” of integration time (the combined exposure

time total). 150” is approximately 2 and a half minutes – that is a lot of

light gathering! But there is another reason why between 10 – 15 is ideal –

during that shooting time – the stars above are moving – well changing position

as it is us on Earth who are moving beneath them. Anyway, the stars positions

will change significantly, the more exposures you take. Keep it simple!

It is the opposite when doing deep sky astrophotography –

the more images you stack, the better the final image is likely to be. With no

foreground to consider, you just must periodically reframe your target back

into the middle of your frame.

What about the foreground element in these milky way shots?

If I am star stacking, I make it a personal rule that

I am doing a separate foreground image, from, as far as possible, the

same tripod position and ball head angle. I am exposing for the foreground

specifically, not worried about star trailing and will probably be thinking

about hyperfocal distance or focus stacking. I will be using a lower ISO. I may

well try and take each exposure at a shutter speed of 1 – 4 minutes. I’ll be

watching the histogram with an eagle eye. In saying all this, a friend, also a

beginner, prefers to go for one long shot using the hyperfocal distance method

– so a shot somewhere around 4 – 10 minutes. I’ve not tried this approach – I

would worry about something moving within the shot during that time. For

example, on my south coast, there are plenty of fishing boats out at night – a

moving fishing boat will leave a significant trail across a 5-minute image!

I have explained these techniques regarding foreground

images in a little more detail in my previous post on camera settings for milky

way photography, which you can access here: https://undersouthwestskies.blogspot.com/2025/02/beginners-guide-to-taking-your-first_20.html

What are the advantages and disadvantages of the star

stacking approach?

Advantages:

·

more integration time but with benefit of

narrower apertures and shorter shutter speeds

·

reduced noise visible in final image which means

more detail is revealed and a better noise to signal ratio – this is because

multiple photos average out the noise resulting in clearer images

·

stacking software tends to remove satellite and

airplane trails (not always, but most of the time)

·

pin point sharp stars

·

increased detail for post editing work

especially with regard to colour accuracy

Disadvantages:

·

the time it takes to do multiple exposures

·

potential alignment issues if there has been

wind movement during the taking of the images; some star trailing if you left

too longer gap between the multiple exposures

·

increased post editing time – extra steps and

complexity using some of the software; and you must raise your game in terms of

understanding some more complex editing techniques (which is my current BIG

problem!)

·

potential loss of detail in the foreground – my

sequator images always appear with blurry foregrounds which are dark and

lacking in detail – hence my shifting to taking a stacked star sky image and a

separate stacked or single long exposure foreground image and blending them

post editing to one image

·

over aggressive smoothing and averaging during

stacking software processing – leading to an over smooth image which lacks

milky way/star detail

What software will you need to stack the images you

collect?

There are three pieces of software that can stack your

collected images

·

DeepSkyStacker – free and great for sky

shots with no foreground

·

Sequator – for images which are

predominately sky and a small amount of foreground (around 10% or so) Windows platform

·

Starry Landscape Stacker for Mac users

I will do future posts soon about using Sequator (for

beginners) and a similar post for DeepSkyStacker – as I use windows platforms. It

will be part of my post about post editing work flow for a milky way image. Although

I won’t do anything on using Starry Landscape Stacker – I will post some useful

blogs and YouTube tutorials which give details for Mac users to follow.

How can we use a star tracker to gain our milky way

image?

I love my star trackers. I have two – an Ioptron Skytracker

Pro and a Skywatcher Star Adventurer 2i Pro. The former I use for milky way

imaging; the latter for that and for deep sky astrophotography as well. I am

considering an upgrade of the SWSA2i to a SWSA gti GOTO model but that is all

the subject of a future post!

So, if you are new to the concept of star trackers –

what are they?

Trackers go between your camera and your tripod and they

move your camera in rotation with the Earth so that your stars are followed

precisely with your camera and there is no star trailing. Basically, a tracker

is motorised and allows you to compensate for the rotation of the Earth.

It brings huge benefits:

·

You gain far longer exposures – I can easily get

up to 3 – 4 minutes on the SWSA2i with no problem. Using my milky way lens – I

can get 5 minutes+ easily if I wished.

·

That is a huge amount of light capture and a

higher signal to noise ratio for a single exposure.

·

It results in images with less visible noise ad

better colour accuracy

·

Images have more detail within the sky and are

sharper throughout. Perfect!

·

Moreover, I can use narrower apertures and lower

ISO’s – so I can go to ISO 800/1600 maximum consistently. Narrower apertures

also lead to less aberrations and vignetting

I wrote a previous post on how I set up my SWSA2i with step-by-step

guidance:

https://undersouthwestskies.blogspot.com/2025/02/beginners-guide-on-how-to-set-up-and.html

Here are my steps:

1.

Level my tripod – I have a bubble level on my

tripod but I also use a small spirit level as well.

2.

Attach my equatorial wedge mount to the tripod –

I don’t use the wedge that came with the SWSA – it was the first thing I

replaced as I found the original insufficiently precise for my deep sky

astrophotography – instead I use a William Optics wedge. Far superior – well

engineered. However, I want to stress that for milky way photography with

smaller lenses and camera weights – I found the original wedge was more than

satisfactory. The wedge by the way is

also known as an altitude-azimuth mount! One of the things you must ensure on

such a wedge is that you have set your latitude – your angular elevation. Don’t

forget to do this.

3.

The tracker mount now goes on top of the wedge

and I make sure it is securely mounted and that the level of the tripod hasn’t

changed.

4.

At this point I might add in my optional

counterweight kit – to balance my lens/camera rig and reduce wear and tear on

the motor itself.

5.

Before going any further, I will now carry out

the Polar Alignment procedure using the little polar illuminator which comes

with the SWSA – I will outline this process in more detail later in this post.

I also use a green laser pen to line up with Polaris – mine attaches to the

viewfinder on the tracker – making it so easy.

6.

Having ensured an accurate polar alignment, I

now attach the base plate and ball head to the tracker mount. I prefer a ball

head but you might use some other accessory to attach your camera – a two-way

head; a MSM Z plate etc. Be very, very gentle – try not to move the tripod or

mount even a fraction – otherwise your polar alignment will be out and you will

have to start the set up again.

7.

On goes my camera/lens combo. I use a L bracket

on my DSLR (see previous post on camera settings). I add on any accessories –

so dummy battery pack, intervalometer etc. However, this is where you can throw

out your polar alignment so,

8.

Redo your polar alignment or at the very least

re-check it again. Fine tuning may be required.

9.

Now do some test shots – I turn the tracker on

and do a 30” and 60” test shot to see that the tracker is working properly and

that there is no star trailing. Zoom in to the review image – check the

corners, the centre – are stars pin point sharp dots? All being well – I now do

test shots at 120” and 180” as well. Pinpoint dot stars – then I am ready to

go.

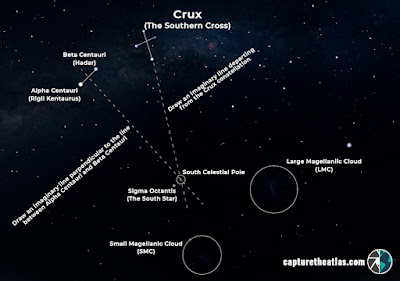

What is polar aligning?

A tracker has to have its rotational axis aligned with the

north celestial pole (NCP) or the south celestial pole (SCP). In the northern hemisphere

– we can use Polaris which sits close to the NCP and this is what I am focusing

on now in this blog post. Getting sharp pin point stars really does rely on

getting polar alignment correct.

If I use my 14mm Samyang lens, then I can get away with just

a rough alignment to Polaris. I use my green laser pen which attaches to my

tracker polar scope. Quick and easy.

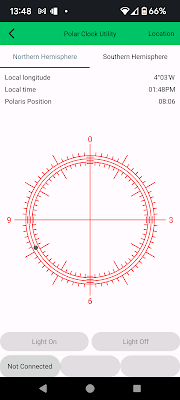

For a precise polar

alignment, I will use the polar illuminator, the green laser pen and an app that

comes with the SWSA tracker. It shows precisely where to place Polaris in my

polar scope reticule for any given time in a particular day. I will adjust both altitude and azimuth knobs

until I get this precise locating of Polaris.

When this adjustment has been made and my various knobs have been

tightened, I check that my hemisphere switch is set to north.

What are my base astro settings and additional

equipment for tracked images of the milky way?

· Aperture F/2.8 although do some test shots to see which aperture gives you best result. There is a case to be made for stopping down to something like F/4.0 - you can do longer shutter speeds to make up for this - the narrower aperture will bring better focused, sharper sky and greater depth of field within a scene

·

Focal length 14 – 35mm max

·

Shutter speed 120 – 180” normally. Sometimes I

will go up to 240 or 300”.

·

ISO 800 (although I often find my Canon 800D

performs better at ISO 1600 for some strange reason) If it is windy – reduce your

shutter speed length and increase your ISO a little.

·

Check your histogram – most of the information

should be in the midtones zone. Zoom into one of the nebula that will appear in

your milky way core image an see if that is correctly exposed and detailed – if

so – all is good

·

Remember a tracker will blur a landscape element

– so if you use a tracker – separate sky and switch off tracker for separate foreground

images to later blend post editing.

·

I use an app with my tracker that also controls

my camera settings – you made need an intervalometer. Have a lens warmer on

standby as well just in case of high humidity/fog. You camera will get warm taking

longer and more numerous exposures.

I hope this blog post has given you an overview of stacking and tracking techniques. I found the videos below particularly helpful.

As always, any mistakes, please forgive me - post a correction in the comment box below and I will get it sorted in the main post text above. Similarly, any further tips, thoughts or observations on tracking and stacking for milky way images, let me know below.

It just remains for me to wish you clear skies - stay safe, have fun

Steve

No comments:

Post a Comment